YES, APPARENTLY if poor people would just change these 20 things, then they wouldn’t be so poor. Silly them.

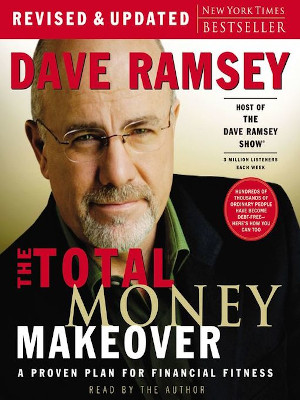

If you keep up with what Christian bloggers, tweeters and prominent Facebookers are linking to and talking about right now you might have noticed people talking about an article called “20 Things the Rich Do Every Day.” Although penned by Tim Corley, the list was posted at Dave Ramsey’s website, evidently endorsed by Mr Ramsey. That was a mistake.

The list, based on a survey of 361 people, has attracted some criticism, and one article that is getting about as much circulation as the original is a critical response from Rachel Held Evans. I have very briefly skim read her response (I say this as a disclaimer, lest anyone think that I am presuming to be familiar with what she says, which I am not). What has followed is plenty of discussion, some of it fairly heated, about who is right, along with plenty of discussion about the list Ramsey posted. Some have accused Held Evans of opportunistically attacking Ramsey because of an ideological disagreement (about which I know nothing and which I will ignore).

I’m not in America and I don’t really know who’s who in the American Evangelical “scene” when it comes to popular social and economic commentary. I know of Rachel Held Evans only vaguely: She’s a successful Christian author, she really doesn’t seem to like Evangelicals, she interviews people, and in articles she does have a tendency to be rather unkind to those with whom she doesn’t agree. That’s literally all I knew about her until this disagreement started doing the rounds. I had never heard of Dave Ramsey (or Tim Corley) at all until I became aware of this article. What I know about him now is that he has done a lot of work giving middle class people and families the hard word about how to get out of debt and get their finances under control. In the interests of full disclosure I should also add that I am fiscally conservative. I am not what anybody could (justifiably, I think) call somebody with a “liberal” or “left wing” outlook on economic policy or society, although to some extent I realise that this is a matter of perspective. Doubtless a pure libertarian would think that I believe in “big government,” and a social democrat (do you use that term in America?) would probably think that I am virtually a libertarian. I have also lived, with a family in tow, on welfare for a couple of periods of my life, between study and work. While I was studying and for several years since I finished studying (I finished study in 2007) my family lived well below the median household income, living below what is in New Zealand regarded as the poverty line (whether it deserved to be called poverty or not is another matter). In relatively recent history this has changed, and while I am not affluent by any means (well over a third of my gross income disappears into rent and we qualify for family assistance), I would qualify as middle class (paying off debt that I accumulated while I was not middle class, some of which was acquired in order to move to the city in which I now live, where I got my current job, which is the main reason I would now consider myself middle-class).

With all my disclaimers and disclosures out of the way, then, here’s my opinion on the list itself. First, here is the list:

1. 70% of wealthy eat less than 300 junk food calories per day. 97% of poor people eat more than 300 junk food calories per day. 23% of wealthy gamble. 52% of poor people gamble.

2. 80% of wealthy are focused on accomplishing some single goal. Only 12% of the poor do this.

3. 76% of wealthy exercise aerobically four days a week. 23% of poor do this.

4. 63% of wealthy listen to audio books during commute to work vs. 5% of poor people.

5. 81% of wealthy maintain a to-do list vs. 19% of poor.

6. 63% of wealthy parents make their children read two or more non-fiction books a month vs. 3% of poor.

7. 70% of wealthy parents make their children volunteer 10 hours or more a month vs. 3% of poor.

8. 80% of wealthy make Happy Birthday calls vs. 11% of poor.

9. 67% of wealthy write down their goals vs. 17% of poor.

10. 88% of wealthy read 30 minutes or more each day for education or career reasons vs. 2% of poor.

11. 6% of wealthy say what’s on their mind vs. 69% of poor.

12.79% of wealthy network five hours or more each month vs. 16% of poor.

13. 67% of wealthy watch one hour or less of TV every day vs. 23% of poor.

14. 6% of wealthy watch reality TV vs. 78% of poor.

15. 44% of wealthy wake up three hours before work starts vs. 3% of poor.

16. 74% of wealthy teach good daily success habits to their children vs. 1% of poor.

17. 84% of wealthy believe good habits create opportunity luck vs. 4% of poor.

18. 76% of wealthy believe bad habits create detrimental luck vs. 9% of poor.

19. 86% of wealthy believe in lifelong educational self-improvement vs. 5% of poor.

20. 86% of wealthy love to read vs. 26% of poor.

Agreement

It’s generally expected that a response to an article will focus on disagreement or concern. This is usually the case (and is here too), but I want to first say that there are things here that I think we should all agree with.

We should plan ahead. Having specific goals and lists of things to accomplish is a way of doing this. Constantly living in react mode and not living proactively is very bad in all sorts of ways, psychologically and in terms of what you can achieve. We should teach our children positive habits, both explicitly and by good example. I’m sure my family is sick of hearing me go on about planning and being accountable for what they do. Saying what’s on your mind (while using discretion and wisdom) is good. Gambling is bad. Spending your money on junk food is wasteful. Teaching your children to read non-fiction is good for their future. All of these, I agree, are habits that promote better wellbeing, including financial wellbeing, whether for us or our children. That these are good habits is something of a truism.

[citation needed]

That being said, I have to say that I simply don’t believe some of these claims. What’s the source? A survey of 361 people? To put it gently, that doesn’t provide us with much confidence. How do we know that only 12 per cent of poor people are focused on achieving a goal? Or that 96 per cent of poor people don’t believe that bad habits lead to unfortunate outcomes? Says who? I commute to work by train most days, and I’d say that most of the people who travel with me are middle to upper-middle class (based on clothing, jewellery and the suburbs at which they get on the train, anyway). And although I don’t know what all of them are doing, as I look around I’m quite certain that nearly all of them are not listening to an audio book. So what is the origin of the claim that “63% of wealthy listen to audio books during commute to work vs. 5% of poor people”? My train trips to work are as scientific as this tiny survey, and they don’t paint the same picture at all.

If this rather pat sounding list of self-help advice is to be worth anything, its claims must be true. But are they? I doubt it. Source please.

Out of Touch, Cause and Effect

The list of habits that rich people have is meant to draw attention to good habits; things that we should do in anticipation of good results. Ramsey confirms that this is the intention here by responding to criticism, saying: “This list simply says your choices cause results. You reap what you sow” [emphasis added]. The choices listed here are the choices to that the wealthy are making, and the results, presumably, have something to do with being wealthy (or, conversely, with being poor). Why else would the comparison be one between wealthy and poor? So that’s what this list was meant to show us: Some choices that people make (or do not make), choices that produce results in terms of whether or not you’re wealthy (or not, if you don’t make them). Of course no single one of these choices would make the difference by itself. But all of them produce some part of the “result.”

There are points in our lives, where like the two of swords, we must make a difficult choice in order to move forward at all. And while many people believe that tarot cards are used exclusively for fortune telling, they can also become an helpful part of how we can make decisions. Truthfully the art of love tarot reading is significantly more complex than describing the outcomes of making one choice or another. In this article, we’ll be briefly discussing some tips for using tarot cards for making decisions, as well as giving you a spread that can help clarify the significance of making one choice or another for you.

But the implied direction of the causation in some of these examples is very questionable. Here are some examples.

I go to the gym. As I look around at the people on treadmills, exercise bikes, elliptical trainers and rowers, at the risk of stereotyping based on appearances, I don’t think many or perhaps any of them would qualify as poor. And there’s a good reason for that. Poor people can’t afford gym memberships. It’s not rocket science.

The luxury of slipping away from the office in the middle of the day to use that inner-city gym, or visiting the gym in your home suburb in the evening after work, is unlikely to be either high on the list of priorities of how to use one’s already scarce money, and may not even be a possibility due to time. If you work as a cleaner for an agency and get sent to buildings all over town or if you work a labouring job in an industrial area or on the roads (etc), slipping out for a long enough time during the day to go for that jog or visit the gym just isn’t possible. And as for the idea that people should “just make time. It’s worth it. Go for a decent run after you get home,” come one. Think a bit harder about the people you’re talking to. Consider the possibility that poor people don’t earn as much per hour as wealthy people – a novel concept I know. Consider that they may need to work longer hours to make ends meet, to travel further (townhouses aren’t cheap you know). They may be a solo parent who doesn’t have a partner who can look after the children. And so on. Be creative. Try hard to imagine the circumstances that might be their “normal.” You might have to apply some effort, depending on who you are.

In other words, the wealthy are likely to dedicate time to aerobic exercise more often because they can. Being wealthy leads to more freedom and more exercise, not the other way around.

Consider gambling. What is the relationship between being poor and gambling? It isn’t obvious. Do wealthy people gamble themselves into poverty? Sure, I have no doubt they do. But ask another question: Who is more likely to feel trapped and desperate, the rich or the poor? Surely the answer is obvious. It’s not obvious that poor people who (for example) buy lottery tickets are poor in part because they buy lottery tickets. Could that money be better spent? Probably, but if they weren’t poor they would be less likely to see the lottery as a possible way out. Is gambling a cause or a symptom of poverty? Sometimes it is one, sometimes the other and sometimes both.

What about watching too much reality TV? Wouldn’t time be better spent out at a museum, or fishing with friends or colleagues (fit that under “networking”), or taking the kids bowling, or going on a drive in the country (listening to audiobooks), or something else? No doubt it would. But most things in life, contrary to cliché, are not free. By comparison, watching television is pretty cheap. Now granted, there are other activities that are cheaper: Playing cards or chess, going for a walk in one’s own neighbourhood (not always advisable for the poor in the evening) or something else. But if you take all the ways that a person can spend their time out and then remove all the options that cost, it should be pretty obvious that watching television will now occupy a larger proportion of the options. People don’t fail to be rich because they watch TV. They watch TV because there are fewer things for them to do. Sure, maybe that means they will then watch too much.

It may be comfortable to stereotype poor people as too lazy to get out of bed in the morning, but the reality is that poor people are more likely to work multiple jobs and to have just gone to bed at the time the wealthy get up, three hours before their work starts.

Waking up three hours before work starts. This one actually made me a little angry. As Paul Gorsky pointed out in his article “The Myth of the Culture of Poverty”1 , “According to the Economic Policy Institute (2002), poor working adults spend more hours working each week than their wealthier counterparts.” It may be comfortable to stereotype poor people as too lazy to get out of bed in the morning, but the reality is that poor people are more likely to work multiple jobs and to have just gone to bed at the time the wealthy get up, three hours before their work starts. I recommend reading that article to shatter a few of the myths that people believe about the unwealthy.

Or lastly, think about education. It apparently counts against the poor on this list that unlike the wealthy, they don’t engage in “lifelong educational improvement.” We don’t know just what the author has in mind here, but try to imagine how crushing the following scenario is: Through no fault of your own, you’re from a poor family. You want to get a commerce degree, but higher education is expensive (assume that you live somewhere in the USA). You manage to get a job at a diner where you don’t need any qualifications to work, so you can save some money for your education. Before long, you realise that even though you’re working 45 hours a week, the minimum wage enables you to meet all your expenses and there’s really not a lot left over. How are you going to pay for your degree and also have enough to live on? You certainly can’t work 45 hours a week while you’re studying. Maybe you can swing 30 hours a week if you live like a monk, studying in all of your other time. And that’s just not going to cut it, money-wise. You’re going to have to save for quite a few years. Some of your peers aren’t from poor families, and they had college funds. So while you are working 45 hour weeks on the minimum wage, not sure if you’ll ever get that degree you want, they are studying and graduating, moving into much better-paid jobs (and getting gym memberships). Even if the best-case scenario works out, and you eventually manage to save enough, you’re looking at being behind by 5-10 years in the race. Minimum, and 10 is more likely than 5. That’s at least 5-10 years’ worth of decent income that you’re not getting.

The reality is that education costs. What it costs and whether you can do it will depend on a number of things including where you live, but Ramsey is in an American context. This is to say nothing at all about the way in which a person’s formative years have a lasting effect on their future. But the truth is that there are people who would like to be in higher education who are not, and there are people who are forced to focus on more basic necessities and never even dream about what they would do if they had the opportunity to pursue higher education. Is their problem that they just disregard life-long education? For a lot of people that turns out to be a pretty callous description.

This is just a portrayal of rich people as nicer, better people. If there is a cause, perhaps we are supposed to think that the general awfulness and stupidity of poor people is the cause of both their poverty and their contempt for people on their birthdays.

Even if the very worst imaginable stereotypes about poor people are true, those suggested in this list and those that are not, some of these comparisons seem quite irrelevant in terms of choices causing effects. Maybe they are lazy people who have no thoughts about the next five minutes of their life, never mind the next five years. Maybe they invest absolutely nothing in their children and simply don’t think about the live they lives. Ridiculous, I know, but assume it for a moment. Now look at an item on this list: Rich people are more likely to make a birthday phone call. Oh! Well that will change something now, won’t it? It’s difficult to see any meaningful cause even suggested here. This is just a portrayal of rich people as nicer, better people. If there is a cause, perhaps we are supposed to think that the general awfulness and stupidity of poor people is the cause of both their poverty and their contempt for people on their birthdays.

In responding to (or attacking, see below) his critics, Dave is careful to stress that he and his wife used to be poor. And since he was poor and got rich, the implication seems to be, he knows what he is talking about, because what happened to him can happen for others too if they would only follow the principles he describes. I’m not familiar with his wider body of work, so I can’t comment on that too much, but I am told by those familiar with his work that it is very good (in fact some have said that although this list was a mistake, we should just ignore that mistake because of all the other good things he has said). But it is very easy to forget from whence one has come, especially when their current place in life is very far from where they started, as is the case here. I used to be a toddler, but I can barely recall what it was like. Even if I could, I have gotten very accustomed to not being a toddler.

I think that this is what is going on in this list of habits. Maybe these are great habits. But there is an important sense in which they are the habits of people who are wealthy – or who at least are not poor. This is what the balanced life of a wealthy person will look like. They will use the opportunities they have when it comes to taking time out for exercise, getting out of the house with the kids, travelling further or paying more for better quality food, investing more in education and so on.

These are indicators of wellbeing, not causes. Poor people don’t live in the world of being wealthy, and to call them to simply start practicing the habits of those that do is neither compassionate nor reasonable.

Blame

The fact that the claims in this list themselves may appear somewhat dubious, compounded by the fact that it is not obvious that we are really looking at causes of poverty (or the causes of not being “wealthy”) at all, and that really some of the things listed here are the symptoms, rather than the causes, of overall wellbeing, along with some of the negative behaviour on the “not wealthy” side of the equation here can leave an unpleasant impression. That impression, whether intentional or not, is that whether a person is wealthy or not depends on whether or not they are a good and wise person. A person who makes the choice to do the things that wealthy people do (some of which they are more likely to do because they are wealthy, remember), and because they lack “character” (a term that Mr Ramsey uses in this context).

Of course it is true that there is bad character and foolish behaviour that will likely make you poor. But it would be logically fallacious to infer that this means that being poor is therefore the result of bad character and foolish behaviour.2 In defending the list against criticism, Ramsey emphasises that in the first world, the choices we make are the main reason for our circumstances. Although I use the term “dogma” in a neutral light (I certainly believe some dogma myself), the idea that in general everything we are is self-made is a dogma that is never defended, even in response to critics.

And yet, this dogma is far from obvious or indisputable. There are more factors at work in our lives than we are aware of, and certainly more than we can control. What family you were born into. How intelligent you are. What suburb you grew up in. What people you were exposed to. Who you had in your life to inspire you. A chance meeting that led to an unlikely but rewarding job opportunity. Just happening to have that teacher who made that comment on that day that changed your attitude to education. The people on that hiring committee who, whether they intended it or not, passed you over because of your colour or religion. The fact that you’re ugly, or an effeminate looking and sounding man. What family you were born into (yes, I’ve already said that, but it is so important). Your natural ability for school, or the kind of work that pays well. There are so many ways in which we are not self-made. What is more, no matter the limits of the power of our sheer will, even if we were somehow magically able to nullify all of these factors (a truly absurd thought), it is not true that those who work for peanuts – all of them – could make choices that would move them on to better things. There are rungs on the professional ladder, and the bottoms rungs must be filled. We need cleaners and street sweepers and people who flip burgers. The market will simply not allow these slots to be vacated, and whether or not you can move on to better and brighter will depend on what the rest of the market is doing. Your sheer desire and determination cannot, in spite of what you may wish for, cause opportunities to spring into existence.

There is a place to point the spotlight directly on the choices that keep people out of wellbeing, of course. Those who were able to get credit may need to be given some tough love about cutting up that card. This is what Ramsey can do. People who could without a doubt make ends meet but who are not doing so because they are wasting what they have need to be sat down and shown a budget, and this is something Ramsey can do. Those who have the resources to pay just a little more in rent to live somewhere that affords them greater opportunity, to move house with the family if need be, to get those clothes for job interviews, to travel to where the opportunities are, to get that education, but who instead are throwing their life away, need to be coached with a strong hand at times.

But to sum up the differences between the wealthy and the poor with a list of good habits that rich people have but poor people don’t is to sum up the discrepancies between different people lives in a painfully naïve way, one that defines the difference in terms of blameworthiness. In answer to a hypothetical question: “Who sinned so that the poor are poor,” Ramsey has a clear answer: They did. He accepts that in a third world setting things may be different. But in a telling move, he lists two causes of poverty in the first world: “1. Personal habits, choices and character” and “2. Oppression by people taking advantage of the poor.” Character? So being unintelligent and unlikely to do well in education is a choice or a character defect? Or being born into poverty with very limited options for how to move away or out is a choice? And then after laying out these three possible causes as the only causes (the third one having to do with “The myriad of problems encountered if born in a third-world economy”), Ramsey states that “If you are broke or poor in the U.S. or a first-world economy, the only variable in the discussion you can personally control is YOU. You can make better choices and have better results.” Now of course this is true as you cannot control things outside of yourself, but that simply drags the issue away from the items on this stupid list. How in the world does noting that rich people go to the gym more or make more birthday calls connect to the idea that if you want to get out of poverty, the only thing you can control is you? This is simply cliché added to irrelevant observation. The fact that you (or more accurately, your decisions) are the only thing you can control does not somehow mean that there are not factors that you cannot control.

To bastardise James 2:14-18 somewhat (while maintaining his voice, I think), “What good is it if you see poor people without transport, living in a bad neighbourhood without easy access to all the shops that you have access to, on the minimum wage and no free time because they work two jobs to raise their three children and you say to them, ‘Choose to eat better, spend more time with your family, get more exercise and study,’ but you do nothing to help them with any of these things? Your fine instruction, without real assistance, is worthless.”

People need more than the will to make some decisions. I guarantee that there are plenty of poor people who have the will to move to a more affluent area where there are better work opportunities, to study part-time or to eat and feed their family better. They don’t need to gain control over the will here. And contrary to Ramsey’s hopelessly misguided supposition that anyone who disagrees with him here is blinded by a “liberal ideology” that has led them away from the Scripture, there is a perfectly biblical ethic of love that comes into play here, and you don’t even have to be a liberal to see it (I certainly am not).

We should call people to make the best decisions that are available to them, yes, but if those decisions are not available to them we should also want to empower them to be able to make those decisions. To bastardise James 2:14-18 somewhat (while maintaining his voice, I think), “What good is it if you see poor people without transport, living in a bad neighbourhood without easy access to all the shops that you have access to, on the minimum wage and no free time because they work two jobs to raise their three children and you say to them, ‘Choose to eat better, spend more time with your family, get more exercise and study,’ but you do nothing to help them with any of these things? Your fine instruction, without real assistance, is worthless.” The hard word that middle-class money wasters need to hear to reign in their finances cannot simply be transferred to the poor who do not even have the money to waste in the first place, and telling them that the even better off people in this world do not make those mistakes is simply not a relevant critique.

As I’m sure Mr Ramsey knows, the Bible has a lot to say about the poor. A lot. And of all the things it says, some themes are more common than others. Blaming poor people for being poor because of their stupidity and bad character isn’t a dominant theme. Showing love for the poor by supporting them in their needs is. And yet this list seems to direct all of our attention to the former, as though poor people are poor because of their choices and instead of help what they really need is to be reminded that they have nobody to blame but themselves. For some reason the biblical writers – although well aware that foolish choices can lead some people into poverty – thought that the other focus was more important.

The Real Problem

BUT – all of that having been said, I’m not even sure that these factors are the root cause of anything here. Although this wasn’t Ramsey’s list, it’s one that he endorses. The truth is, though, I don’t think a whole lot of intellectual capital went into this list, and even less into the act of sharing it. To see people writing about it, talking about it and seriously criticising it (as I am!) is a bit like seeing them writing about, talking about and criticism a motivational poster that sounds good and probably wasn’t intended for close scrutiny. Don’t gamble – Right! Too much reality TV is bad! Achieve goals! Pass on good advice (whatever that might consist of) to your children – Amen!

As I said, I know almost nothing about Dave Ramsey. What I have heard since discovering this storm in a teacup, however, from his critics including Evans as well as from those who think he is wonderful, is that quite apart from this soundbite-packed list, he has a much wider work of helping people to plan their way out of debt and into better financial wellbeing, and that he has changed many, many lives for the better. But, and here’s the point, this list is not representative of that careful, thoughtful and, he maintains, biblical work. It was a nice-sounding thing (nice sounding to those who aren’t poor, anyway) that came his way and he reproduced it at his blog in much the same way that one so easily clicks “share” or “retweet” at a social media website.

But now people have paid close attention to it. They’ve scrutinised it in terms of what it literally says, whether or not it is strictly true, on its innuendoes and implications about rich people and poor people (mostly the latter). And instead of acknowledging that the original list was actually pretty shallow and not capable of being applied in any rigorous way, the amygdala has kicked in, the battle lines are being drawn and it is on. This conversation only exists because we sometimes (unwisely, I think) summarise ourselves with the thoughtless, we treat the shallow with seriousness (at no point have I seen Ramsey’s critics saying that really this is just a case of putting the trite on a pedestal), and we absolutely do not back down. And that leads to my last concern.

Responding to criticism

Nobody likes to be criticised. Or at least, most of us dislike it, especially when that criticism is vocal and pointed – and even more so when that criticism gets a lot of coverage. But how we respond to that criticism is important, especially if we are somebody who enjoys the reputation of being somebody with wisdom who teaches others how to live. And that is definitely how Dave Ramsey sees himself – and understandably so, because he does a lot of teaching.

As I type this I think back nervously about how I have responded to serious criticism in the past. The reaction to the various criticisms that are being circulated is what struck me more than any of the above. It begins as follows: “There has been so much negative and ignorant response to the above list that I felt I needed to respond and teach; that is what teachers do.” My critics are so ignorant that I need to teach them. Really? “My team and I are loving teachers who understand that people’s best shot at having a better life is to make better choices, have better habits, and grow their character.” That’s great (and I don’t say that with a sarcastic voice – that really is great). But to respond to criticism fairly immediately by blasting critics as “ignorant” and “immature,” referring to them as hailing from a place “where immature people now study, reflect, research and communicate in only 140 characters” (i.e. Twitter) is uncharitable to put it mildly. That somebody offers a critical comment on Twitter hardly indicates that a Twitter comment is the extent of their reading. Presumably they at least read the list itself, or the longer response to it. The sad thing is that while I have heard good things about what Mr Ramsey does, much of the praise from others is undone by this outburst to the point where I am now very unlikely to seek his advice. A fairly shallow set of apparent rules that basically blames the disadvantaged for every disadvantage from which they suffer while showing a painfully out-of-touch approach to the realities with which they live, followed by a pretty nasty rant about critics does not exactly scream wisdom – even if he has plenty of it on a good day. Perhaps it’s a timely moment to hear from St James again (chapter 3):

But the wisdom from above is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, open to reason, full of mercy and good fruits, impartial and sincere. And a harvest of righteousness is sown in peace by those who make peace.

So there you have it. I have entered the fray.

Glenn Peoples

- Educational Leadership 65:7 (2008),32-36. [↩]

- Specifically, this is the formal logical fallacy of “affirming the consequent.” [↩]

Michelle

Thank you for entering the fray. Your analyses are spot-on in my opinion. I’ll resist the temptation to repeat what you’ve said (I love the sound of my voice), except to reiterate that calling your reader’s criticisms “negative” and “ignorant” is what teachers AVOID. Teachers realize that the act of teaching is rectifying misunderstanding, not placing blame for it. I know this because I am a teacher. I teach and I will never be wealthy, even though I do practice several of those rich-people habits.

bethyada

Glenn, I don’t have a lot of time to write substantially at the moment, so some brief thoughts for now.

Your lack of reading of Ramsey seems to have coloured your perception of this post detrimentally. I dont’ mean he writes well except for this, I mean you aren’t reading this right.

There is a cultural problem between the US and NZ here. The US celebrates excellence, we tend to see it as arrogance. Yet we have our own problem with the Tall Poppy Syndrome (outside sport).

You read blame whereas many may read encouragement to do better. I don’t read it as blame at all. I read it as if I have money problems these are issues that may be in my life which perhaps I can change. A lot of Dave’s readers read him like that. This is because Dave is very self-depreciating. He writes about all the stupid things he did, and others who have made similar mistakes find it easy to own to their own mistakes.

Phylis Maddox

Two things: No, ‘social democrat’ isn’t really used in the US – too easy to confuse it with the formal Democratic Party. ‘Social liberal’ is the likely equivalent (political terminology can often be difficult to define with any precision).

As to the article, like the controversy I think we’re really over-reading here. It’s a small sample size, pretty obviously not meant for use as a study tool and looks more like the equivalent of a financial puff piece than actual advice. It looks to me as more of a ‘for what it’s worth’ space filler than ‘you should live like this in order to get rich’. I’m a bit more familiar with Ramsey’s work and I’ve never heard him even imply that the poor are all poor because they are lazy, et al. He does take issue with living beyond your means for any group – but I’ve never heard him offer any such negative characterizations so I don’t think the ‘get up three hours early’ has anything to do with Ramsey believing the poor are lazy. To be honest, I took it differently – more ‘wealthy people tend to invest in themselves with their time/resources’ not ‘poor people should get up unrealistically early despite longer working hours and pay for expensive gyms beyond their means’. The former might be an attainable goal if put into realistic perspective but my impression is that the reader is intended to make use of the list as they will – or not.

FYI: it is possible to obtain financial aid in the form of Federal grants or (backed) loans and/or public and private scholarships (not just for the A+ students) in the US – most students use some form of financial aid.

Glenn

Yeah, I’m more than willing to believe the best of the work that Dave normally does. I could probably benefit from it! 🙂

T'sinadree

Glenn,

I’m not familiar with Dave Ramsey or his work, or if your interpretation of him is correct, but speaking as someone from the US, the attitude you describe (i.e., blaming character for being poor) is, unfortunately, exceedingly common here.

Also, concerning bethyada’s mention of the US’s celebration of excellence, this is, in my opinion, more of an excuse to justify our idols of individualism and self-determination.

As for Phylis Maddox’s comment concerning financial aid, it’s true that this can be obtained. However, this has caused a huge debt crisis here, and it stays with the student for many, many years after graduation.

Jeff

Glenn, thanks- beautifully written and absolutely on the mark. As a Canadian (and atheist, coincidentally) I grew up relatively poor and find myself doing well enough now- that said, the American or North American propensity to ascribe credit to the wealthy, blame to the “free riders” (the Republican Party seems to adore the creation of “others’ to blame- those others are taking your taxes, spending those taxes on health care etc) is unfortunate.

Loved your article. When we can all see people as people, and resist the quick generalization we’ll be much better off.

Pastor D Ojumbe

“and atheist, coincidentally”

Not a coincidence, really. Glenn is clearly slipping into the liberal atheist ideology. He does not accept that the root cause of all poverty is personal folly, unbelief and sin. I am with my brother Dave Ramsey in pointing out that “choices have causes.” This is the Bible’s view, and this blog post slides into humanistic fatalism.

Mark

“Pastor,” insightful comment like Glenn’s here is what keeps alive the possibility that non-believers like me may actually one day see eye to eye with Glenn on the God question.

Comments like yours (and to some extent, Dave Ramsey’s) are part of what makes this less likely. Is it even worthy of critique? Probably not.