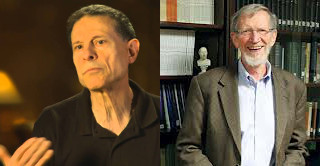

As I’ve been saying a bit about Plantinga in the podcast recently, it’s fitting to comment on something that I recently found online. Evan Fales, back in 1994, wrote a book review critical of Alvin Plantinga’s Warrant and Proper Function. The review was originally published in the journal Mind, and you can read it here.

As I’ve been saying a bit about Plantinga in the podcast recently, it’s fitting to comment on something that I recently found online. Evan Fales, back in 1994, wrote a book review critical of Alvin Plantinga’s Warrant and Proper Function. The review was originally published in the journal Mind, and you can read it here.

For those not already familiar with Plantinga’s epistemology, his idea of warrant (that is, the thing that makes a belief into knowledge, and not just a lucky true belief) involves the further idea of proper function. Fales, like me, takes Plantinga to hold to a variety of what’s known as reliabilism (although not everyone construes Plantinga that way – but that doesn’t matter just now). For Plantinga, we have warrant for our beliefs if they are formed by a properly functioning set of belief forming faculties, functioning in a truth aimed way, in an enviromnment to which they are well suited, in accordance with a design plan. His argument is aimed at the conclusion that if atheism were true, knowledge would be impossible, since our belief forming faculties – indeed all of our faculties – would not have a proper function, much less a design plan.

But Evan Fales thinks he has demonstrated a flaw in Plantinga’s view of knowledge. Here I will comment on only one such attempt on Fales’ part. He poses the following counter example:

An example: a game of “telephone” in which A is to whisper something he knows in B’s ear, B whispers it to C, and so on to the last person, Z, who accepts what he hears because he takes it to be what A said (and correctly takes A to know whereof he speaks). Everyone’s hearing, speech, and cognitive systems are working sufficiently well, and the environment is sufficiently ideal, to meet Plantinga’s requirements for warrant–warrant so high that, when combined with truth, it yields knowledge. Then given the way warrant is transmitted by testimony, Z’s belief that A said “Plato was Greek”, and hence, Z’s belief that Plato was Greek, both count as knowledge on Plantinga’s account, provided that both these beliefs are true. But now suppose that (improbably), some slippage occurs in the transmission of the message: halfway to Z, it has become “Pluto is green”. By sheer luck, however, the slippage is reversed: by the time Y whispers it in Z’s ear, “Pluto is green” has transmuted into “Plato was Greek”. Surely, here, Z does not know what A said, or know that it is true merely because A said it.

Perhaps I am missing something, but this seems to pretty obviously misrepresent Plantinga’s view of knowledge. In fact the scenario described does not meet Plantinga’s criteria for warrant. Plantinga is quite clear that what is needed is a belief forming faculty/structure (call it what you will) that is, among other things, functioning properly in a truth aimed way in an environment for which it is well suited and in accordance with a design plan. Here, that belief forming process or structure, it would appear, is a series of people relying on something whispered very quietly to them. The whole point of this “telephone” game is to see if a message can be transmitted in spite of circumstances that are not conducive to good communication. Why else would the game be a challenge? A structure consisting of all these people is not at all well suited to preserving the integrity of information in this way. There is a design plan at all all right, a design to make things harder rather than easier.

It is quite irrelevant that each individual in the game has hearing, speech and cognitive systems that are functioning properly, unless Fales is willing to say that those systems and senses were designed to function in an environment like this game. Even theists do not say this, let alone atheists! And when the chain of people as a whole is considered as the process of getting information to the last player, any claim that Plantinga’s conditions for warrant and consequently knowledge are met here simply do not seem plausible at all.

Moreover, it is fairly clear that if “slippage” occurs, we can no longer call the transmission process a properly functioning one. This is like saying that if a person endorses empiricism, crudely described as the view that we gain knowledge via sense experience, then we are committing to the view that a person with impaired vision should always trust what he sees.

These are not sophisticated replies, because the mistake seems so rudimentary. How could Fales think that this is a credible critique?

Glenn Peoples

Andrew

All that Fales presented was a good example of a gettier type counter example

Glenn

Exactly Andrew. This is the kind of “justification” that Plantinga’s concept of warrant is developed specifically to remedy.

Andrew

That’s why I found it rather remarkable that Fales should think it sufficient to take out Plantinga’s argument.