A few days ago I got home from a speaking tour in Hamilton, Muriwai Beach, Avondale (for those outside of New Zealand, those two are both in the Auckland region) and Tauranga. Fifteen talks over eight days! All the talks were very well received, and the discussions that followed were excellent.

A few days ago I got home from a speaking tour in Hamilton, Muriwai Beach, Avondale (for those outside of New Zealand, those two are both in the Auckland region) and Tauranga. Fifteen talks over eight days! All the talks were very well received, and the discussions that followed were excellent.

The overall theme of the talks was faith and reason, unpacking some of the ways in which Christians have used reason to commend what they believe as true, along with some of the implications of Christianity actually being true. The opening talk at a couple of venues was directly about the crucial role of reason within the Christian faith, reflecting on the observation, among others, that “commitment without reflection is fanaticism.” The change of this site’s address to rightreason.org is motivated by this commitment to the reasonable discussion and defence of what we believe and why (whether overly Christian or not).

Against this backdrop, imagine the sense of irony that swept over me yet again when I arrived home, checked my email and read the following message (we’ll call the author J, who has consented to this email being made public).

How can you keep up the pretense that you know about life after death. You mock common sense. You trade on peoples [sic] fears of the dark and the unknown to put forward a controlling elitist superior position.

Reason in everyday decisions must prevail over blind faith

Deep sigh. I’m pretending to know about life after death? Fear of the dark? I’m an elitist? I advocate blind faith and shun reason? Where to even begin! I’m not sharing this because I think the writer is uniquely wrong. I’m sharing it because it illustrates something I see a fair bit of. When is the last time I wrote anything about life after death? I don’t recall. Is that what prompted this? If so, why didn’t the writer say anything about the content of my comments, whatever they were? I don’t know. And where did this “blind faith” deal come from? Did I say anything in support of blind faith lately? No, that’s just not something I would have said. In fact I’ve just gotten back from eight days of speaking directly against any such thing. What prompted these comments? Maybe I’m assuming too much. Maybe nothing prompted these comments. But that’s not likely. From nothing, nothing comes!

I asked J what prompted these comments. The answer: “What prompts my comment is the increasing threat of violence that seems to accompany a breakdown in opposing sides communicating with each other.”

I just blinked. This is what prompted the claim that I am only pretending to know that there’s life after death? This is why someone thought that I mock common sense? The actions of dangerous groups who hurt others in the name of the religion is why I need to come to realise that we shouldn’t have blind faith, and we should use reason? How could anyone think this?

Actually, I lie. I didn’t just blink. And I didn’t think “how could anyone think this.” There was no deep sigh. And I didn’t sit there wondering about all the different combinations of comments I might have made that led to this. The above actually ties in to part of one of the talks I gave while away last week. It would be a mistake to read the above email and then try to piece together the process of reason that someone might have gone through to arrive at the apparent conclusions they did. That would be an over-analysis. This sort of thing appears in blog comments sections and social media sites every day, and reason has nothing at all to do with it. The reason I couldn’t discern the rational connection between anything I might have said and the response quoted above is that there literally isn’t one. These comments simply weren’t prompted by the concerns the author gives. Sorry if that’s you, but they were not. I’m not accusing the author of these comments of just thinking this through badly and making wrong connection. Comments like this were really never intended as arguments or observations – because they were barely intended at all, any more than a sudden, almost spontaneous violent reaction that a racist person might have when they walk around the corner and are suddenly met by a person of colour – or for that matter when you suddenly see a spider or a mouse run across the floor – or, somewhat differently, when the opposing team runs out onto the sport field and – regardless of how good the team is – is met with a chorus of jeers and boos. You don’t sit there, reflect on that team’s merits based on the past year’s performance, come up with the appropriate description to offer, say it out loud to yourself to make sure it comes across as intelligent, reasoned and measured, then shout out something like “Although you’re technically very adept, due to my local loyalties I hope you lose to my home team – nothing personal!” We overlook this. You cheer for your team. It’s sport – it’s fun. Watching it need not involve much by way of rational reflection, you can get enthusiastic and kick back a little.

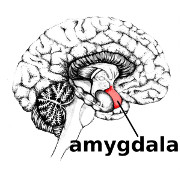

The trouble arises when our instincts – whether the “amygdala hijack,” that overwhelming fight-or-flight response, or our learned team loyalty – kick in, short-circuit our reasoned method of interaction and we simply lash out in ways that seem frankly irrelevant to the occasion that prompted our lashing out. So you’ve formed a stance (not necessarily a carefully thought-out intellectual position, but an attitude, a way of reacting, an emotional disposition) on religion in general (without making any serious effort to distinguish between very different issues like terrorism or theological discourse, so long as religion of some sort is somehow involved in both of them), later seeing an instance of religious belief, then reacting and letting all of that built up attitude just burst out, regardless of any genuine connection between what we say and the occasion that gave rise to it. When asked what brought these comments on, the author reached for a completely irrelevant concern about religious violence, flattering himself that really there had been a rational process that gave rise to the comments at all. And he’s not alone – this is the way we rationalise such reactions all the time.

Are there people who do harmful things in the name of religion? Absolutely. Does that have anything to do with my views on life after death? Of course not. And does it at all imply that I’m a liar, just keeping up a pretence to believe in life after death when really I know it’s a load of rubbish? Again, nobody rationally thinks this. And lastly, does any of this at all suggest that I – on account of holding religious beliefs – think that we should prefer blind faith (whatever that is) to reason? The question virtually answers itself – of course not. None of this is about reason. It’s psychology playing out, and little else.

So much of what passes for interaction over religious issues, however, is just like this. Oh, so you’re religious? Bam – the chemicals start flowing. React! Defend (against an imagined attack). Attack (an imagined target). Of course religion isn’t the only issue where this happens. Neither are the anti-religious the only people who are capable of this sort of thing. My point is just that it is often a mistake to go straight to an analysis of the content of this kind of inexplicable reaction out of the blue. This is why I didn’t do that with my correspondent. I would have been trying to understand a string of thought out argument that simply wasn’t there. The intellectual case would be constructed to justify the reaction that had already occurred.

If I had treated all of this differently, and assumed that it was all an accurate description of someone’s genuine concerns about religion, followed up with some questions that genuinely sought to deal with those concerns, instead of recognising it as a non-rational knee-jerk reaction to the fact that I’m a Christian, coupled with an after the fact rationalisation of that reaction as really prompted by sensible considerations, then there’s a certain proverb that I should have heeded: “Do not answer a fool according to his folly.” In this context that means: Don’t get sucked in. See what’s going on. Otherwise you’ll go back and forth, each time a new rationalistion will be offered to you as though it was there all along, the scrip will get more and more silly and entrenched, and days or weeks later you’ll be sitting there wondering “How on earth did I get into this? Where does it end?!”

To give succinct answers to the questions:

How can I keep up a pretence of believing in life after death? I don’t have to. It isn’t a pretence. You might think that I am wrong, but I do, in fact, believe in life after death and one of the ways of justifying such belief is by appealing to the reasons to believe in the resurrection of Jesus (which was the subject of one of my recent talks). If you wish to say in a roundabout what that I am mistaken, however, it takes more than sneering. J, how about you engage with the case and share where you think it fails?

Do I mock common sense? Not that I can tell. In fact I think that common sense about morality or the existence of God is inherent to many of the things I believe.

Do I advocate an elitist superior position? Hardly, this is just bluster.

And lastly, should reason prevail over blind faith? Absolutely! Here we can happily agree. The fact is, I think that there are good reasons to believe as I do, J. If you spend a bit of time at the blog, reading through the archives or listening to the podcast, you’ll find out what some of those reasons are.

But J, let’s not kid ourselves that you came to me because you were concerned about the rise of religious violence and the communication breakdown that this fosters. You were venting in the total absence of careful, rational thought. This is blind rejection – easily as bad as blind faith – and here I can only echo your own thoughts: Reason should prevail over this.

Glenn Peoples

Jason

Nicely said Glenn.

Mark Webster Hall

It likely qualifies as being a mite overcharitable in this case, Glenn, but hasn’t your correspondent hit the nail precisely on the sharp-end here in and with his claim that Christian beliefs concerning life after death constitute a mockery of common sense? Couldn’t we (in lieu of overanalysis) take your accuser’s fly-by-night boutade as an accidentally accurate encapsulation of much that offends the naturalist in the Christian position, namely that the latter takes its stand against all deaths (first, second, and more besides) and thereby grounds all of its scandalous truths in a new kind of reason, a kind of reason that is in an important sense noncontinuous with perchance all non-Christian philosophical traditions feeding off the “common sense” in question. It is thus critically the refusal of such philosophical traditions to mock the common sense of death that marks them apart from Christian strands of knowledge and enfeebles them accordingly.

This branding (by virtue of a specific refusal to mock) is perhaps at its bluntest, its most callous, with regard to (say, post-Thomist) ethics, where as John Milbank notes, secular reason ultimately valorises death as a necessary constraint upon wanton spillages of the Good: “[One] mark of [secular] morality is complicity with death … Death for death to secure life against death [ … ] this is ‘morality’, this is ‘ethics’. Without death, there would be no need to be good, violence would be but sado-masochistic fun, and not even that, since death alone gives such play its spice, so apparent play would be reduced to no more than nursery give-and-take, a virtual utopia without consequences. So ethics must covertly celebrate death, for only our fragility elicits our virtue” (“The Word Made Strange: Theology, Language, Culture”, p. 223).

Thus? Ahem … (cough! splutter!) … regardless of how facetious and shortsighted the polemical context in which the default, yet-again-on-his-high-horse-yet-again-exasperated-with-the-theologican’s-patience atheist may be involved, I believe that, at least with cooey of public holidays, his complicity with death (and the like) is something about which he quite plausibly deserves to know.