Here’s a 48-minute presentation on the Canon of Scripture. The short story is that the Protestants did not just decide to throw out seven books of the Bible. use of the protocanon (the shorter version of the canon) is as old as the Christian faith itself!

Category: Christianity Page 1 of 5

The Ministry of Education is trying to force Bethlehem College, a Christian school, to change its statement of belief – a statement that reflects Christian beliefs. Specifically, they are trying to compel the school to remove their statement that they believe marriage is the union of a man and a woman, on the grounds that this discriminates against those who do not share this view or who are in a relationship outside of this definition. On the face of it, this is a shocking thing for a Government agency to do and an obvious affront to the right of the school to freely state its belief on a matter that is hardly a surprise. This is, after all, the Christian view of marriage. But here’s the thing: The grounds on which the Ministry is trying to make the school change its statement of belief on the one hand, and the reason the ministry is being urged to do so on the other, are quite different animals.

It’s a situation, I think, where a government agency is fronting what seem like reasonable grounds for their demand, while serving a more sinister purpose. That’s how a slightly cynical person might read this situation (and cynicism is perhaps wise in this situation).

We have a tendency to think our own sins aren’t that big a deal, or to find ways to downplay them or overlook them, while taking serious issue with those awful people on the other side of ideological divides. I’m something of an Evangelical Christian, and I’m very aware that it happens here in abundance.

Speaking of Evangelicals…. It’s cool to hate Evangelicals. You probably know that. I entered the word “Evangelicals” in a search of Twitter, to see what results I got. I got this:

Now it’s just a tweet, a random individual’s prejudice on display. I know. But everyone who spends time on social media (and doesn’t inhabit a circle of friends numbering in single digits) knows that actually, what you find is an absolutely constant, voluminous stream of a mixture of all sorts: Vitriol, contempt, general slander, obviously unreasonable generalisations, conspiracy theories, revolting claims, and so on. Don’t take my word for it. When I carried out this search, this is what I saw immediately. I did not have to go looking for these. These were among the first results:

Don’t think that you, a Christian, can avoid the teaching of the historic Christian faith by saying “but that’s just what conservative Christians think.” Christianity is conservative.

It was a year or two ago, and I was having a conversation with a young Christian with an impressive degree of unearned confidence (and let’s be honest, many of us have been that guy at some stage). We had talked briefly about universalism, a view he holds and I do not. Due to the generally unproductive nature of the exchange, I didn’t commit many of the details to memory. I had little hope of a fruitful conversation, I’ll admit, due to his (somewhat justified) reputation among his social media peers for disagreeableness and dismissiveness, along with extraordinary disdain for those he dubs “conservatives.” A couple of comments did, however, stand out to me. They raise an issue that I have often thought about in other contexts.

Apparently people like personal stories, so here goes.

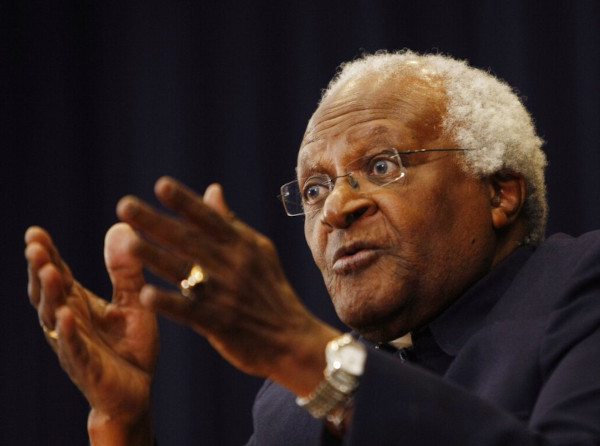

It can be difficult to admit that your hero left a legacy that is very… mixed.

You’re a villain if you have anything but unfettered praise to offer for Archbishop Desmond Tutu, now that he has passed away, aged 90. He was a great voice for justice against Apartheid. That is how many in the world will remember him, and understandably so. It is impossible to look back on so much of what he had to say about racial segregation in South Africa in the early 1980s and not be impressed. Just read this account from Jim Wallis:

I understand the appeal of looking for that perfect church that is the “right fit” for you. I’ve engaged in that search, too. But as much as I understand that drive, I’ve been getting pushback against that from my own thoughts and growing convictions. In engaging in this sort of quest for the church that’s “just right for me,” we’re short-changing ourselves, we’re short-changing the local church we aren’t participating in, and we’re potentially distorting the wider Church.

“There are far, far better things ahead than any we leave behind.” ~ C S Lewis

Interesting – and wonderful – things are happening in the Anglican Communion. I’ve been slow to acknowledge – actually, slow to see – that these are not isolated events, but part of a wider movement.

There are a couple of things I want to say about some of these recent developments. Some of it is on the more sorrowful side, as we see ugly outpourings of bitterness, misrepresentation, and ill-will from some quarters (sadly, from the leaders of the Church to which I belong) as they see the reach of their power shrinking and God’s Church growing beyond it. But that can wait. First, I want to hesitantly and cautiously invite you to rejoice and give thanks. I’m hesitant and cautious only because I’m only just beginning to see and to realise how good these developments are – I am sure that my confidence will grow.

What should we make of what people say about why they don’t believe, and how should the Church respond?

According to a report commissioned by the Wilberforce Foundation, just over half (55%) of New Zealanders do not identify with a “main” religion. 35% described themselves has being neither spiritual nor religious, and 33% identify with Christianity.

Along with an increase among those with no religious or spiritual beliefs, the study shows an increase in ignorance about Christianity. More than one in five people know nothing about the Church in New Zealand, and 9% of respondents know no Christians. This growth in non-exposure is reflected in the makeup of the group that does not identify as religious or spiritual. When comparing a person’s current status (religious/none religious) with the home environment in which they were raised, the single largest combination (26% of respondents) is “Never been religious: I was shaped in a non-religious household and am non-religious to this day.”

Don’t create a church’s stance on marriage in order to make people happy or stop them from leaving.

In early 2017 (when I started writing this article, since which time it has sat gathering dust) the general Synod of the Church of England voted on same-sex marriage. Well, sort of. The General Synod voted not to endorse a report by the House of Bishops on Same-sex marriage. The report affirmed the biblical and historic Christian view that marriage is the union of a man and a woman. To be specific, there are three houses in the General Synod. The House of Bishops voted in favour of the report. The House of the Laity voted in favour of the report. But the support of all three houses is required, and the House of Clergy alone voted not to endorse the report, confirming the widely-suspected reality that the clergy are the more liberal element of the Church of England.

There were many issues discussed at the time and obviously I wasn’t present. On Twitter however I encountered a speech by activist Lucy Gorman. When I saw it I raised a criticism of it, but Lucy quickly blocked me so I can no longer see the portion of the speech that was shared there. Ever the believer in dialogue, I found this a little disappointing (especially since she had initially asked me for my view on the suicide of people who felt hurt by the church, but then told me that she didn’t really want to talk about it with me and blocked me).

So let me bring the issue to you, dear reader.

Partly a product of social media, the way we talk about those with whom we disagree has changed a lot.

In particular, at the risk of sounding partisan, here is the way I see those who view themselves as “progressive” (what a terrible name to give yourself) engaging religious conservatism: Instead of talking to people about why they disagree and why they think people of a conservative bent should change their minds or behaviour, they talk about them to the world. When they do so they are not critically engaging with them (even if they tell us that this is what they are doing). Instead they are serving the social function of shaming them, not so that they will change their mind, but so that they will be afraid of speaking.

Many progressive Christians, if I have observed things correctly, think that they are the real followers of Jesus (who, we are told, was an inclusive, tolerant, liberal-minded progressive), while religious conservatives are more like the religious hypocrites from whom Jesus distanced himself. Sweeping generalisations are usually wrong if taken as hard and fast rules. This description is true of many religious conservatives, no doubt There are plenty of them, after all. But to a large extent it is self-flattering nonsense. While many progressives like to say that religious conservatives “pick and choose” which commands of Jesus they follow, sometimes it’s helpful to hold up a mirror to this outlook, if only because of its irrepressible self-confidence in being real, authentic, pure-as-the-driven-snow, Jesus-following Christianity, along with its current occupation of a position of social power, something Christians are justified in being suspicious of (let’s remember that it’s not just a worrying combination when it’s manifested in the religious right).

Progressive Christianity, had it existed in the first century, would have found opportunities to shame Jesus himself.