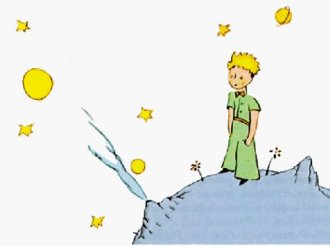

My favourite children’s book right now is The Little Prince, by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. I’m currently reading it to my son. He’s old enough to read it himself (he recently turned 10 – how the years have flown by!), but I’m making the most of reading to him while he still lets me – long may those years last!

Sometimes Children’s books (like the chronicles of Narnia, or this one) have a way of presenting profound philosophical points in such a perfect way. I doubt that all such points are self-explanatory to their young audience, which is yet more reason to think that children’s stories like this one are best when read to children as well as by them, because a really good story benefits the reader as much as the listener.

Anyway, to the point: Part IV of The Little Prince, the narrator, the man who met the Little Prince, introduces us to the fact that the Prince is from Asteroid B-612. But the narrator assures us that he’s just telling us this as a matter of fact, and not for the sake of “the grown-ups and their ways.” For you see,

Grown-ups love figures. When you tell them that you have made a new friend, they never say to you, “What does his voice sound like? What games does he love best? Does he collect butterflies?” Instead, they demand: “How old is he? How many brothers and sisters does has he? How much does he weigh? How much money does his father make?” Only from these figures do they think they have learned anything about him.

If you were to say to the grown-ups: “I saw a beautiful house made of rosy brick, with geraniums in the windows and doves on the roof,” they would not be able to get any idea of the house at all. You would have to say to them, “I saw a house that cost £4,000.” Then they would exclaim: “Oh, what a pretty house that is!”

Just so, you might say to them: “The proof that the little prince existed is that he was charming, that he laughed, and that he was looking for a sheep. If anybody wants a sheep, then that is proof that he exists.” And what good would it do to tell them that? They would shrug their shoulders and treat you like a child. But if you said to them: “The planet he came from is Asteroid B-612,” then they would be convinced, and leave you in peace from their questions.

They are like that. One must not hold it against them. Children should always show great forbearance toward grown-up people.

But certainly, for us who understand life, figures are a matter of indifference. I should have liked to begin this story in the fashion of the fairy-tales. I should have liked to say: “Once upon a time there was a little prince who lived on a planet that was scarcely any bigger than himself, and who had need of a friend…”

To those who understand life, that would have given a much greater air of truth to my story.

For I do not want any one to read my book carelessly. I have suffered too much grief in setting down these memories. Six years have passed since my friend went away from me, with his sheep. If I try to describe him here, it is to make sure that I shall not forget him. To forget a friend is sad. Not everyone has had a friend. And if I forget him, I may become like the grown-ups who are no longer interested in anything but figures.

As someone with some familiarity with – and great appreciation for – the writings of Alvin Plantinga, and just as someone who thinks that we can know that God exists without being able to convince anyone, this stood out to me immediately as really profound.

Christians believe (or at least I hope I’m not the only one who believes this) that in some really important way, we know God, and that God, to some extent, has made himself known to us. Take a philosophically unsophisticated person to whom God has personally made Himself known as loving and forgiving, and so forth. Given that God really has done so, what kind of objection is it to say to such a person, “but how can this have happened when we don’t even have any hard evidence that God exists?” In these circumstances, that God is loving and forgiving (and so forth) is evidence that he exists, because you can’t be loving and forgiving – or anything else – unless you exist.

Of course, if someone forbids the possibility that the narrator ever knew the little prince, or that God could ever have actually made himself known, this will just sound false. All the more reason to think that (a very strong form of) evidentialism leaves something to be desired.