Several months ago a Catholic friend of mine made a comment about a church. It was an Anglican church that every year seeks attention by putting up potentially offensive posters that have been known in the past to mock tradition Christian theology (the church has a reputation as being theologically liberal). My friend did not suggest that this showed that Anglicanism itself was wrong (it’s important to add that).

In a rather unfortunate display of something I see far too often when churches and their mistakes are being discussed, a fellow came along and suggested that (my paraphrase) this is what happens when churches abandon God’s true church that Jesus founded, the Catholic church, and they don’t follow the papacy, which is the true repository of apostolic teaching. Then the argument was clearly stated: Without the English Reformation and the Anglican Church, the above incident would not have happened, and hence the Anglican church shouldn’t exist and the Reformation was a mistake.

So I replied to this stranger:

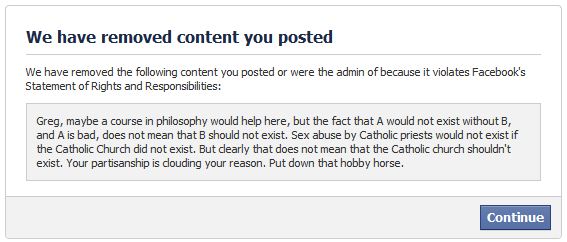

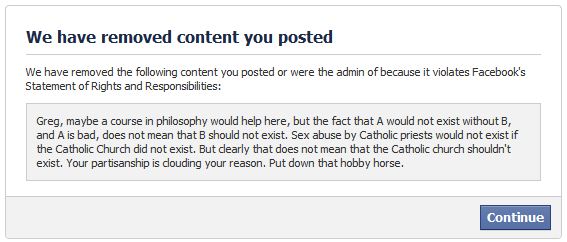

Greg, maybe a course in philosophy would help here, but the fact that A would not exist without B, and A is bad, does not mean that B should not exist. Sex abuse by Catholic priests would not exist if the Catholic Church did not exist. But clearly that does not mean that the Catholic church shouldn’t exist. Your partisanship is clouding your reason. Put down that hobby horse.

Of course the same is true of any church: Anglicans, Presbyterians, Baptists and so on. Churches, just like any organisation, provide a place where people can do the same bad things people would do no matter where they were. But this fellow was Catholic, so the above example was more appropriate.

Now what happened next? Was I offered a reason to re-think the logic of this counter-example? No. I received a message from Mr Matheson telling me that he didn’t “like” my comment, and asked that it be removed. Naturally, I declined. The only reasons to dislike the above statement might be that one sees that it undercuts their argument but can’t think of a good way to respond (as I believe was the case here), or one misunderstands the statement to mean its opposite, namely that sex abuse in the Catholic church does show that the Catholic church shouldn’t exist – although I struggle to see how anyone could honestly believe that this is what was meant.

Imagine my surprise then, when I logged into Facebook today and saw this:

There’s no recourse to this – no way of appealing or objecting to this bizarre decision, so that’s really the end of the matter – not that I mind. It’s just a Facebook conversation with a stranger after all. You can read Facebook’s community standards here, where I think you’ll see that in fact my comment doesn’t get close to violating any of them. As far as I can see this is nothing more than a case of intellectual cowardice in the utmost: Running scared from a rebuttal and then having it hidden from public view so that nobody sees how one’s argument was undermined.

But if this incident highlights anything, it offers advice to my Catholic friends: Don’t argue against Protestantism (or anything else) this way. Yes, the Reformation, like the counter-reformation, like Vatican II, like movements within medieval Catholicism, like movements within Protestantism, the scientific revolution, and indeed like the very existence of the Catholic church itself, may have made some unfortunate things possible. But that never, by itself, shows that something is wrong, that it should not exist, or that it should not have happened. If you do, you may end up with somebody offering a response that you really wish the world couldn’t see.

Glenn Peoples

Does physicalism about human persons pose a problem for the Christian doctrine of the incarnation? I don’t think so.

Does physicalism about human persons pose a problem for the Christian doctrine of the incarnation? I don’t think so.

I’ve never been coy about the fact that I’m looking for academic work. Through the blog, the podcast, publications and public speaking I’m trying to raise my profile in the hopes that all these things will help me to make that contact, get the right person to notice, land that job, get that title, improve finances, and set me off on a rewarding career. Of course I wouldn’t shun any of those things. I’m not stupid. But I’m not just an academic and a Christian. I’m a Christian academic. That doesn’t mean that the only subjects that interest me are overtly about God (although given that my subjects of interest are philosophy and theology that is certainly a common theme in the subjects that do interest me). It means that I do academia as a Christian. My goals and my attitudes need to be continually shaped into goals and attitudes that are not just compatible with a Christian outlook, but which are an integral part of it.

I’ve never been coy about the fact that I’m looking for academic work. Through the blog, the podcast, publications and public speaking I’m trying to raise my profile in the hopes that all these things will help me to make that contact, get the right person to notice, land that job, get that title, improve finances, and set me off on a rewarding career. Of course I wouldn’t shun any of those things. I’m not stupid. But I’m not just an academic and a Christian. I’m a Christian academic. That doesn’t mean that the only subjects that interest me are overtly about God (although given that my subjects of interest are philosophy and theology that is certainly a common theme in the subjects that do interest me). It means that I do academia as a Christian. My goals and my attitudes need to be continually shaped into goals and attitudes that are not just compatible with a Christian outlook, but which are an integral part of it.

Here it is, the last podcast episode for 2011. This time I’m looking at “the “evil god challenge” as posed by Stephen Law in a fairly recent article by that name. Isn’t the evidence for a good God really no better or worse than the evidence that an evil god? In short, no. Here I explain why I think (as I suspect many may think) that the evil god challenges has major philosophical shortcomings, in spite of being an argument worthy of our attention.

Here it is, the last podcast episode for 2011. This time I’m looking at “the “evil god challenge” as posed by Stephen Law in a fairly recent article by that name. Isn’t the evidence for a good God really no better or worse than the evidence that an evil god? In short, no. Here I explain why I think (as I suspect many may think) that the evil god challenges has major philosophical shortcomings, in spite of being an argument worthy of our attention.