This is the second instalment in the “nuts and bolts” series of blog posts, where I take some of the “nuts and bolts,” the basic concepts employed within philosophy (and later I suppose I’ll use examples in theology as well) and explain them for those who might not be as familiar with them as people who encounter them a lot.

Recently while I was giving a public talk on the contentious issue of abortion, I made reference to the idea of “numerical identity.” In context, I was explaining that even though the features of a fetus will change considerably over time during gestation, and will continue to change considerably after birth as well, although its qualities at one point are not identical to its qualities at a later point, it is still the same entity. In technical terms, I explained, it remains “numerically identical” the whole time, and so I, an adult, am numerically identical to a fetus that once lived.

This term caused a bit of confusion for a couple of people in attendance. For example, one man thought that “numerically identical” just meant “a set made up of the same number of things.” He objected that my comments summarised above committed me to the claim that I am identical to one of my hairs. After all, there’s just one of me, and if I pluck out a hair, there’s just one of it too, so the two things would be numerically identical (after all, 1 = 1)! So I’ve decided to make this second nuts and bolts blog post all about the concept of numerical identity. It’s not the most riveting of subjects, but a pretty important one in philosophy one nonetheless.

So what is identity? Although it’s a term used in philosophy, it certainly isn’t unique to the field of philosophy. Philosophy isn’t an abstract, arcane discipline unto itself. It’s an approach to concepts and ideas that actually apply to the whole variety of disciplines, subjects and issues that all of us interact with in our lives as we use or employ language, science, medicine, as we engage new beliefs, come up with new ideas about the universe, decide how to evaluate theories, pursue justice and so on. Philosophers have had plenty to say as they have explained and discussed this concept of identity that all of use use in everyday speech and life, whether we realise it or not. For example, it gets used in police line ups (e.g. “looking at these five people, can you identify the man who robbed the bank?”), it gets used in romance novels (e.g. “could this really be the same man I knew all those years ago as a child?”), it gets used in our study of the natural world (e.g. “scientists tagged the salmon so that in the months to come as they tracked its movement, they could identify it as the one they were studying”), it gets used in spy movies (e.g. “my cover was blown. In spite of my changed appearance, the KGB now knew who I really was”), and so on.

Whether we’re aware of it or not, all of these scenarios are taking for granted the most fundamental of all logical laws, namely the law of identity (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_of_identity). It is both simple and obviously correct, and is as follows:

A = A

That’s it. In English, it is best stated this way: “everything is identical with itself” (or ?A = A, “necessarily, everything is identical with itself”). This may seem fairly trivial and obvious, but it requires us to distinguish between two important concepts of identity. The law of identity is referring to what is called “numerical identity,” although there is another way that things can be identical, namely by being “qualitatively identical.”

In order for entities to be qualitatively identical, they must share all the same qualities (i.e. their qualities must be identical). Two perfectly manufactured ping pong balls would be qualitatively identical provided they are made exactly the same way. To see the difference between the two kinds of identity, consider this: Imagine that I showed you those two ping pong balls and asked you to point to one of them. Next, imagine that I were to put those ping pong balls behind my back and switch them between my hands a few times. Then imagine that I held them out to you, one in each hand, and asked you “which one is identical to the one you chose?”

You could react in one of two ways, depending on how you interpreted my question. If you thought I was talking about qualitative identity, you might say “they are BOTH identical with the one I pointed to earlier.” And you’d be more or less right if that was what I meant. But that’s not what I meant. What I’m talking about now is numerical identity. Imagine that unbeknownst to you, each of the ping pong balls had a name, X and Y. The one you had pointed at was Y. In terms of numerical identity, the correct answer to my question is “Y. Y is identical with the ball that I originally pointed to.”

Numerical identity is not about the qualities that a thing (or person) has. It has everything to do with whether something is the same object or entity as another. Qualitative identity on the other hand is something that comes in degrees. Two things can be more similar or less similar. Two ping pong balls are very similar. They are not absolutely the same in all qualities (e.g. including even location), or we would be talking about the same ball after all. But two things can be pretty much qualitatively identical while still being not at all numerically identical. Here’s another example to hopefully make this distinction clear: Imagine that you were a witness to a murder on a cold and dark autumn night. You got a good clear look at the killer standing under a street light. He had a menacing scowl on his face, a long beard, and wild woolly red hair. Now you stand in the dock as a witness as this man stands trial. The prosecution lawyer asks you – “is that man the same person you saw at the scene of the murder?” You look over at the accused man. He has had his hair cut short since that terrible night, and now he’s clean shaven as well. From what you’ve heard, he has changed his attitude as well. He felt so terrible because of what he had done that he has really turned his life around, and now he wouldn’t hurt a flea. Because of all these changes, you say to yourself, he’s not the same man anymore. So you say to the lawyer, “No. That’s not the man I saw that night. He’s different from that man.”

Of course, you can see exactly what’s wrong with this answer. The person in the dock is confusing two different understandings of the word “same,” each of which deals with a different type of identity. This man’s qualities have changed over time, so in a qualitative sense he’s different, but it’s still true that he’s the same man as the murderer in a numerical sense. This could have been easily demonstrated if, on the night of the murder, you branded a number into his rump – the number 75 (Why 75? Well, why not!). That way, when standing in the dock, you could have simply asked the man to drop his trousers, and then you could declare – “Yes, that man has the identity of (i.e. he is identical with) the killer I saw that night. You would have established that whatever changes he might have undergone, he is numerically identical with the killer (unless of course there’s another man with the number 75 branded onto his rear, but we won’t go there).

Stated differently, numerical identity means that if everything in the universe had a different number assigned to it (and only one number), the things that I have in mind share that number (meaning that they aren’t different things, but rather the same thing after all). Take for example the fetus that was in my mother’s uterus six months before I was born. Give it a number (let’s pick 498,178, 895, 659). Then look at me, sitting here typing this. What’s my number? It’s 498,178, 895, 659 – the same number as that fetus. The fetus has kept that number for more than 33 years, and now that fetus sits here, typing. I am therefore numerically identical with a fetus that once existed (of course what exists now is not a fetus but an adult).

So there you have it, the concept of numerical identity.

Glenn Peoples

This episode is a recording of a talk I gave last week at the University of Canterbury on abortion.

This episode is a recording of a talk I gave last week at the University of Canterbury on abortion.

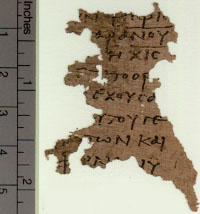

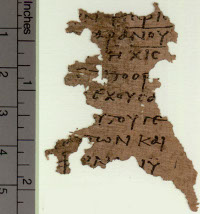

What you might not also be aware of is that some early manuscripts of the book of Revelation – in fact the earliest that we have, such as the fragment found in the

What you might not also be aware of is that some early manuscripts of the book of Revelation – in fact the earliest that we have, such as the fragment found in the