Some time ago I began a series on the notorious biblical passages that form part of the historical discussion about women in positions of leadership in the church. I expressed some reservations there about wading into the subject, because I don’t think many people are interested in what people who disagree with them have to say about this. So I included there some cautions about how I’m going to approach the subject, and specifically about the sorts of objections I’m not interested in. If you plan to read on, and especially if you plan to comment, it might be best to read that post first.

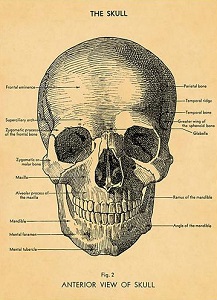

Then I began the series, starting with a look at a word St Paul uses to describe the relationship between men and women, while he is discussing men’s and women’s roles in the churches in Corinth and Ephesus. That word, which he applies to men, is kephalē (κεφαλή), and literally means “head.” In that blog post, I observed that kephalē in the New Testament does not mean “source,” which some say was Paul’s intended meaning, but rather it is used to mean a literal head, or else, when it is used metaphorically, it refers to “preeminence, priority, authority or superiority in some broad sense encompassing shades of these meanings.” That is what the raw data in the New Testament shows us.

This time I will turn to the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Old Testament widely used in early Christianity. You can check the observations I make by seeing for yourself how the word is used there. In the resource I have used for this analysis, kephalē occurs a few hundred times. I have read each of these instances (in English, confirming that kephalē is the word I am observing where this is not clear). I know, doing the groundwork is dry and boring. But you have to do it in order to have any right to tell people what the evidence shows. The approach I am taking here is observing how kephalē is used and describing these “groups” of meaning.

How did St Paul read the creation story?

How did St Paul read the creation story?